Timing and Rate of skeletal maturation in Horses

©2005 By Deb Bennett, Ph.D.

All Horses of All Breeds Mature Skeletally at the Same Rate

There is no such thing as an ‘early maturing’ or ‘slow maturing’ breed of horse. Let me

repeat that: no horse on earth, of any breed, at any time, is or has ever been mature

before the age of six (plus or minus six months). So, for example, the Quarter Horse is

not an “early maturing” breed – and neither is the Arabian a “slow maturing” breed. As

far as their skeletons go, they are the same. This information comes, I know, as a shock

to many people who think starting their colt or filly under saddle at age two is what they

ought to be doing. This begs discussion of (1) what I mean by “mature” and (2) what I

mean by “starting”.

When is a Horse Skeletally Mature?

Just about everybody has heard of the horse’s “growth plates”, and commonly when I

ask them, people tell me that the “growth plates” are somewhere around the horse’s

knees (actually the ones people mean are located at the bottom of the radius-ulna bone

just above the knee). This is what gives rise to the saying that, before riding the horse,

it’s best to wait “until his knees close” (i.e., until the growth plates convert from cartilage

to bone, fusing the epiphysis or bone-end to the diaphysis or bone-shaft). What people

often don’t realize is that there is a “growth plate” on either end of every bone behind

the skull, and in the case of some bones (like the pelvis, which has many “corners”) there

are multiple growth plates.

So do you then have to wait until all these growth plates convert to bone? No. But the

longer you wait, the safer you’ll be. Owners and trainers need to realize there’s a

definite, easy-to-remember schedule of fusion – and then make their decision as to

when to ride the horse based on that rather than on the external appearance of the

horse. For there are some breeds of horse – the Quarter Horse is the premier among

these – which have been bred in such a manner as to look mature long before they

actually are mature. This puts these horses in jeopardy from people who are either

ignorant of the closure schedule, or more interested in their own schedule (for futurities

or other competition) than they are in the welfare of the animal.

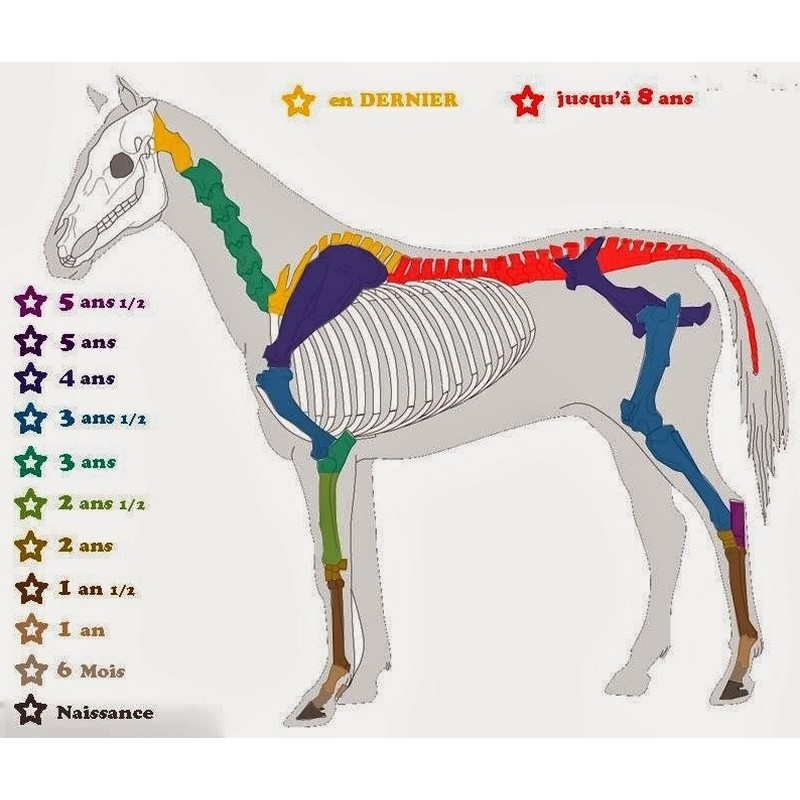

The Schedule of Growth-Plate Conversion to Bone

The process of converting the growth plates to bone goes from the bottom of the animal

up. In other words, the lower down toward the hoofs you look, the earlier the growth

plates will have fused; and the higher up toward the animal’s back you look, the later.

The growth plate at the top of the coffin bone (the most distal bone of the limb) is fused

at birth. What that means is that the coffin bones get no taller after birth (they get much

larger around, though, by another mechanism). That’s the first one. In order after that:

Short pastern – top and bottom between birth and 6 months.

Long pastern – top and bottom between 6 months and one year.

Cannon bone – top and bottom between 8 months and 1.5 years

Small bones of the knee – top and bottom of each, between 1.5 and 2.5 years

Bottom of radius-ulna – between 2 and 2.5 years

Weight-bearing portion of glenoid notch at top of radius – between 2.5 and 3 years

Humerus – top and bottom, between 3 and 3.5 years

Scapula – glenoid or bottom (weight-bearing) portion – between 3.5 and 4 years

Hindlimb – lower portions same as forelimb

Hock – this joint is “late” for as low down as it is; growth plates on the tibial and fibular

tarsals don’t fuse until the animal is four (so the hocks are a known “weak point” –

even the 18th-century literature warns against driving young horses in plow or other

deep or sticky footing, or jumping them up into a heavy load, for danger of spraining

their hocks).

Tibia – top and bottom, between 3 and 3.5 years

Femur – bottom, between 3 and 3.5 years; neck, between 2.5 and 3 years; major and 3rd

trochanters, between 2.5 and 3 years Pelvis – growth plates on the points of hip, peak of

croup (tubera sacrale), and points of buttock (tuber ischii), between 3 and 4 years.

And what do you think is last? The vertebral column, of course. A normal horse has 32

vertebrae between the back of the skull and the root of the dock, and there are several

growth plates on each one, the most important of which is the one capping the centrum.

These do not fuse until the horse is at least 5 ½ years old (and this figure applies to a

small-sized, scrubby, range-raised mare. The taller your horse and the longer its neck,

the later the last fusions will occur. And for a male – is this a surprise? – you add six

months. So, for example, a 17-hand Thoroughbred or Saddlebred or Warmblood gelding

may not be fully mature until his 8th year – something that owners of such individuals

have often told me that they “suspected”).

Significance of the Closure Schedule for Injuries to Back and Neck vs. Limbs

The lateness of vertebral “closure” is most significant for two reasons. One: in no limb

are there 32 growth plates! Two: the growth plates in the limbs are (more or less)

oriented perpendicular to the stress of the load passing through them, while those of the

vertebral chain are oriented parallel to weight placed upon the horse’s back. Bottom

line: you can sprain a horse’s back a lot more easily than you can displace those located

in the limbs.

Here’s another little fact: within the chain of vertebrae, the last to fully close” are those

at the base of the animal’s neck (that’s why the long-necked individual may go past 6

years to achieve full maturity – it’s the base of his neck that is still growing). So you have

to be careful – very careful – not to yank the neck around on your young horse, or get

him in any situation where he strains his neck (i.e., better learn how to get a horse broke

to tie before you ever tie him up, so that there will be no likelihood of him ever pulling

back hard).

Relationship of Skeletal to Sexual Maturity

The other “maturity” question I always get is this: “so how come if my colt is not

skeletally mature at age 2 he can be used at stud and sire a foal?” My answer to that is

this: sure, sweetie, if that’s how you want to define maturity, then every 14 year old boy

is mature. In other words, the ability to achieve an erection, penetrate a mare, and

ejaculate some semen containing live sperm cells occurs before skeletal maturity, both

in our species and in the horse.

However, even if you only looked at sperm counts or other standard measures of sexual

maturity that are used for livestock, you would know that considering a 2 year old a

“stallion” is foolish. Male horses do not achieve the testicular width or weight, quality or

quantity of total ejaculate, or high sperm counts until they’re six. Period. And people

used to know this; that’s why it’s incorrect to refer to any male horse younger than 4 as a

“stallion,” whether he’s in service or not.

Peoples’ confusion on this question is also why we have such things as the Stallion

Rehabilitation Program at Colorado State University or the behavior-modification clinic

at Cornell – because a two year old colt is no more able to “take command” on a mental

or psychological level of the whole process of mating – which involves everything from

“properly” being able to ask the mare’s permission, to actually knowing which end of her

to jump on, to being able to do this while some excited and usually frightened humans

are banging him on the nose with a chain – than is a 14 year old boy.

What Does it Mean to “Start” a Young Horse?

Let us now turn to the second discussion, which is what I mean by “starting” and the

whole history of that. Many people today – at least in our privileged country – do not

realize how hard you can actually work a mature horse – which is very, very hard. But

before you can do that without significantly damaging the animal, you have to wait for

him to mature, which means – waiting until he is four to six years old before asking him

to carry you on his back.

What bad will happen if you put him to work as a riding horse before that? Two

important things – and probably not what you’re thinking of. What is very unlikely to

happen is that you’ll damage the growth plates in his legs. At the worst, there may be

some crushing of the cartilages, but the number of cases of deformed limbs due to early

use is tiny. The cutting-horse futurity people, who are big into riding horses as young as

a year and a half, will tell you this and they are quite correct. Want to damage legs?

There’s a much better way – just overfeed your livestock (you ought to be able to see a

young horse’s ribs – not skeletal, but see ‘em – until he’s two).

Structural damage to the horse’s back from early riding is somewhat easier to produce

than structural damage to his legs. There are some bloodlines (in Standardbreds,

Arabians, and American Saddlebreds) that are known to inherit weak deep

intervertebral ligament sheathing; these animals are especially prone to the early,

sudden onset of “saddle back’” However, individuals belonging to these bloodlines are

by no means the only ones who may have their back “slip” and that’s because, as

mentioned above, the stress of weightbearing on the back passes parallel to its growth

plates as well as parallel to the intervertebral joints. However, despite the fact that I

have provided a photo of one such case for this posting, I want to add that the frequency

of slipped backs in horses under 6 years old is also very low.

So, what’s to worry about? Well…did you ever wish your horse would “round up” a little

better? Collect a little better? Respond to your leg by raising his back, coiling his loins,

and getting his hindquarter up underneath him a little better? The young horse knows,

by feel and by “instinct”, that having a weight on his back puts him in physical jeopardy.

I’m sure that all of you start your youngstock in the most humane and considerate way

that you know how, and just because of that, I assure you that after a little while, your

horse knows exactly what that saddle is and what that situation where you go to mount

him means. And he loves you, and he is wiser than you are, so he allows this. But he

does not allow it foolishly, against his deepest nature, which amounts to a command

from the Creator that he must survive; so when your foot goes in that stirrup, he takes

measures to protect himself.

The measures he takes are the same ones you would take in anticipation of a load

coming onto your back: he stiffens or braces the muscles of his topline, and to help

himself do that he may also brace his legs and hold his breath (“brace” his diaphragm).

The earlier you choose to ride your horse, the more the animal will do this, and the more

often you ride him young, the more you reinforce the necessity of him responding to you

in this way. So please – don’t come crying to me when your six-year-old (that you

started under saddle as a two year old) proves difficult to round up. Any horse that does

not know how to move with his back muscles in release cannot round up.

Bottom line: if you are one of those who equates “starting” with “riding”, then I guess

you better not start your horse until he’s four. That would be the old, traditional,

worldwide view: introduce the horse to equipment (all kinds of equipment and

situations) when he’s two, crawl on and off of him at three, saddle him to begin riding

him and teaching him to guide at four, start teaching him maneuvers or the basics of

whatever job he’s going to do – cavalletti or stops or something beyond trailing cattle –

at five, and he’s on the payroll at six. The old Spanish way of bitting reflected this also,

because the horse’s teeth aren’t mature (the tushes haven’t come in, nor all of the

permanent cheek teeth either) until he’s six.= This is what I’d do if it were my own

horse. I’m at liberty to do that because I’m not on anybody else’s schedule except my

horse’s own schedule. I’m not a participant in futurities or planning to be. Are you? If

you are, well, that’s your business. But most horse owners aren’t futurity competitors.

Please ask yourself: is there any reason that you have to be riding that particular horse

before he’s four?

When I say “start” a horse I do not equate that with riding him. To start a young horse

well is one of the finest tests (and proofs) of superior horsemanship. Anyone who does

not know how to start a horse cannot know how to finish one. You, the owner, therefore

have the following as a minimum list of enjoyable “things to accomplish” together with

your young horse before he’s four years old, when you do start him under saddle:

Comfortable being touched all over. Comfortable: not put-upon nor merely tolerating,

but really looking forward to it.

This includes interior of mouth, muzzle, jowls, ears, sheath/udder, tail, front and hind

feet. Pick ‘em up and they should be floppy.

Knows how to lead up. No fear; no attempt to flee; no drag in the feet; knows that it’s his

job to keep slack in the line all the time.

Manners enough to lead at your shoulder, stop or go when he sees your body get ready

to stop or go; if he spooks, does not jump toward or onto you, will not enter your space

unless he’s specifically invited to do so.

Leads through gate or into stall without charging.

Knows how to tie, may move to the side when spooked but keeps slack in the line all the

time.

Knows how to be ponied.

Carries smooth nonleverage bit in mouth. Lowers head and opens mouth when asked to

take the bit; when unbridled, lowers head and spits the bit out himself.

Will work with a drag (tarp, sack half filled with sand, light tire, or sledge and harness).

Mounts drum or sturdy stand with front feet.

Free longes – comes when called and responds calmly to being driven forward; relaxed

and eager.

When driven, leaves without any sign of fleeing; when stopped, plants hind feet and

coils loins; does not depend on back-drag from your hand to stop him.

Familiar with saddle, saddle blanket, and being girthed and accepts it quietly.

Backs easily, quietly and straight in hand, “one step at a time”.

Loads quietly in horse trailer, unloads by stepping backwards from inside horse trailer

without rearing or rushing.

Various people might like to add to this list. Please feel free, just so long as what you’re

asking your young horse isn’t more than he can physically do. Getting the horse “100%

OK” mentally and emotionally – those are the big areas in successful early training;

most of the physical and athletic skills can come later, when it is fitting.

I’ve had people act, when I gave them the above facts and advice about starting

youngstock, like waiting four years was just more than they could possibly stand. I think

they feel this way because the list of things which they would like to include as necessary

before attempting to ride is very short. Their whole focus is on riding as why they bought

the animal, and they think they have a right to this. Well, the horse – good friend to

mankind that he is – will soon show them what he thinks they have a right to.

According to the traditional method, it would give this:

Introduce any sorts of equipments and situations when they are two years old.

Mount and dismount from their back when they are three.

Begin to get into the saddle and to teach their the direction when they are four.

Teach them their job, whatever it is, when they are five.

So that they are trained when they are six.

One can, to better realize the youth or old age of his horse, converting his actual age in its human equivalent.

In practice, we can almost make a simple multiplication of the horse's age by 3 to get the equivalent in human age. Even its growth stage foal to adulthood is almost proportional to what we know in humans, unlike many animals that adulthood is reached early.

Indeed, it is based on observations of the ages of the horse, veterinarians have established a correlation table to see an equivalent human age:

One can, to better realize the youth or old age of his horse, converting his actual age in its human equivalent.

In practice, we can almost make a simple multiplication of the horse's age by 3 to get the equivalent in human age. Even its growth stage foal to adulthood is almost proportional to what we know in humans, unlike many animals that adulthood is reached early.

Indeed, it is based on observations of the ages of the horse, veterinarians have established a correlation table to see an equivalent human age:

|

horse |

6 months |

8 months |

10 months |

1 year |

2 years |

3 years |

4 years |

5 years |

6 years |

7 years |

|

human |

18 months |

2 years |

2,5 years |

3 years |

6 years |

9 years |

12 years |

15 years |

18 years |

21 years |

|

horse |

8 years |

9 years |

10 years |

12 years |

14 years |

16 years |

18 years |

20 years |

30 years |

40 years |

|

human |

24 years |

27 years |

30 years |

36 years |

42 years |

48 years |

54 years |

60 years |

90 years |

120 years |

Sources:

Equine Studies Institute

A LECUYER Ostéopathe Equin et Humain